The modern states of the Middle East were formed in the twentieth century, with the British Empire playing a key role in shaping their borders. After the First World War, the League of Nations granted former Ottoman Arab lands to the victorious powers as Class A mandates, promising them eventual independence. Britain took control of Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Transjordan—now Iraq, Israel, Palestine, and Jordan. As history has borne out, Britain’s rule in these regions had a lasting impact, influencing their political and social development. In this article, we explore the reasons behind Britain's administration of these specific territories and the consequences of its policies during the interwar period.

- 1. Britain and the Arab Provinces of the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of War

- 2. The Beginnings of War and Britain’s Goals in the Region

- 3. Britain and the Arab National Liberation Movement

- 4. Britain and France: The Secret Partition of Territories

- 5. Britain and the Zionist Movement

- 6. The Formation of the Mandate System

- 7. The Kingdom of Iraq

- 8. The Emergence of Transjordan

- 9. The Fate of Palestine

- 10. What to read

Britain and the Arab Provinces of the Ottoman Empire on the Eve of War

At the start of the First World War, the territories of many modern Middle Eastern states were part of the Ottoman Empire. Since the latter was in deep decline at that time, Great Britaini

The British first occupied Egypt in 1882 and then established a protectorate over it in 1914. Their main goal was to secure control over the Suez Canal, a trade route that was the ‘key’ to India, then a colonial possession of the British Empire. Second, London established itself on the Arabian Peninsula, where it seized southern Yemen and the important port of Aden; it also negotiated a series of treaties with the ruling sheiks of Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait. This was necessary to consolidate their position in the Persian Gulf, which was the shortest maritime route between India and Europe.

Alexandria Bombardment of 1882, the French Consulate (ruins). 1882/Wikimedia Commons

Great Britain also demonstrated a heightened interest in the territory of what was then Mesopotamia, and the future Iraq, which administratively consisted of three Ottoman vilayets, or provinces—Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. Strategically, Mesopotamia was a ‘bridge’ between the Eastern Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean, and the discovery of oil deposits in the Mosul region at the beginning of the twentieth century made Mesopotamia even more attractive to the British.

Other Arab territories, such as modern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, were administratively part of Ottoman vilayets (including Aleppo, Damascus, and Beirut), as well as sanjaksi

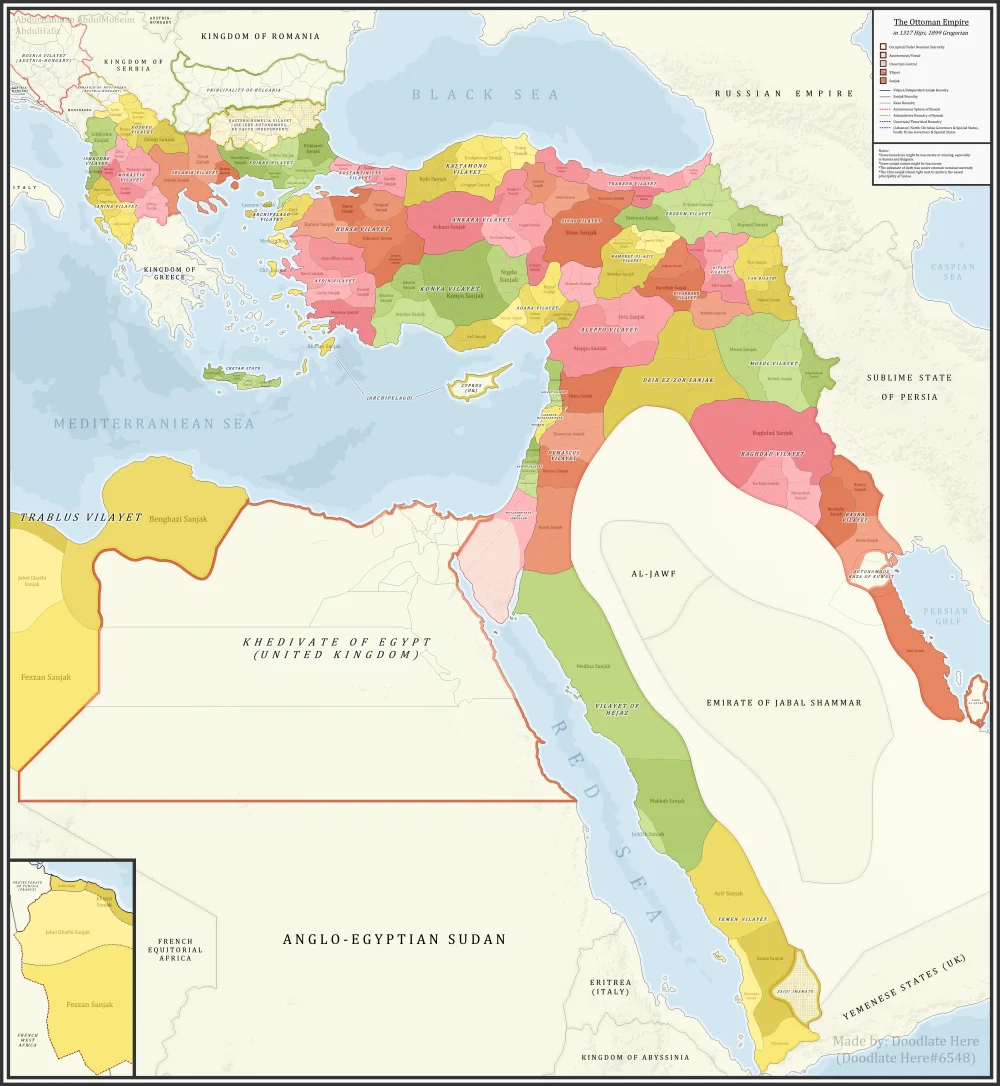

A map showing the borders and administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire in 1899 /Wikimedia Commons

The Arabian Peninsula was nominally under Ottoman control, but in practice, the empire lacked the resources to maintain real authority over this territory. In eastern Arabia, Ottoman influence was weak, limited by Britain’s growing presence and its alliances with local rulers. In the western peninsula, in the Hejazi

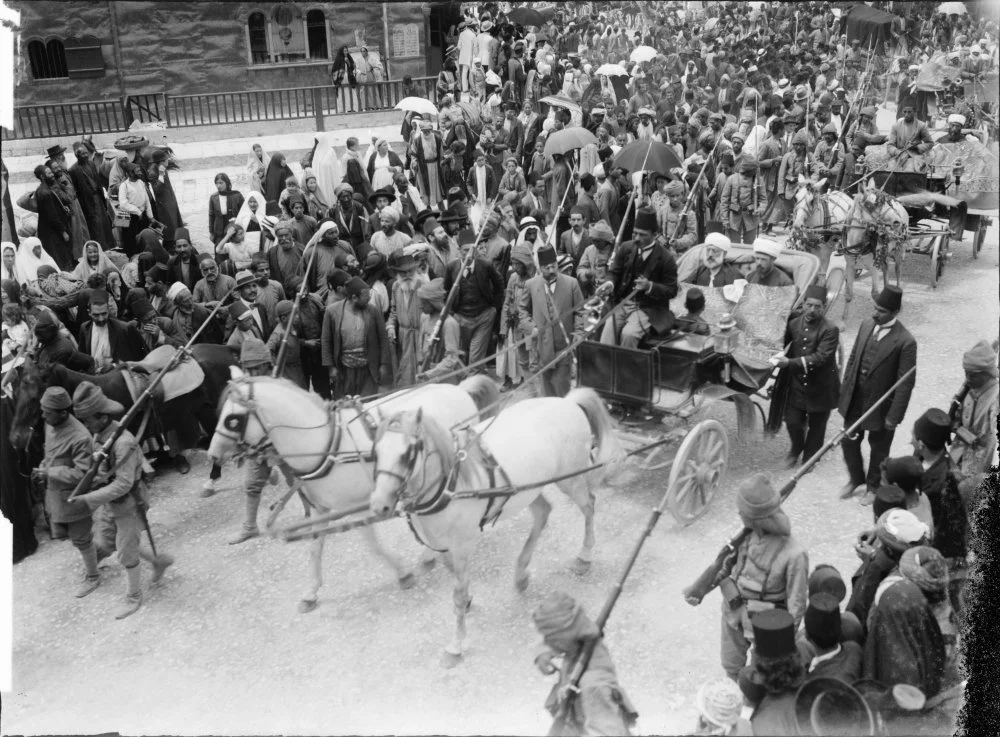

A Holy Carpet brought to Jerusalem by the Sherif of Medina; the Grand Mufti and Sherif in carriage/medium: G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection/Wikimedia Commons

In 1908, Hussein ibn Ali of the Hashemite dynasty became sharif, and like all sharifs, he claimed descent from the Prophet. He saw himself as the future ruler of an independent Hejaz—or even a broader Arab state—and positioned himself as a leader of the Arab nationalist movement.

The Beginnings of War and Britain’s Goals in the Region

Long before military operations in the Middle East had concluded, London began to consider the fate of the Ottoman territories. In 1915, a special committee was formed under the leadership of diplomat Maurice de Bunsen, its main objective to determine whether Britain needed Middle Eastern territories and, if so, which ones would be most beneficial. Indeed, as history shows us, the committee’s conclusions had a decisive impact on the postwar division of the region.

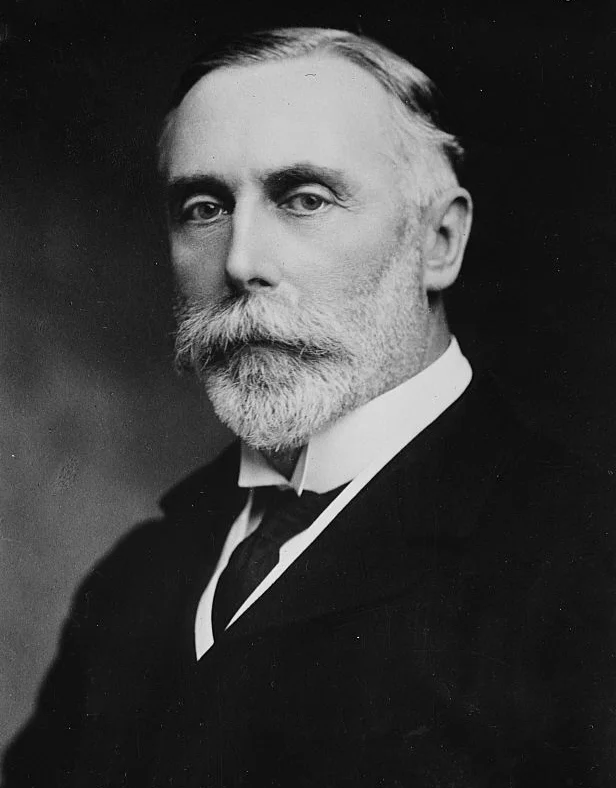

Sir Maurice de Bunsen in 1909/Wikimedia Commons

In broad terms, the committee’s report proposed a ‘solution’ that would both ‘ensure the continued existence of Turkey in Asia and safeguard Britain’s vital interests’. This meant that while the Ottoman Empire would retain its independence, it would become decentralized and lose some of its territories. Meanwhile, Britain would annex the Ottoman vilayets of Basra, Baghdad, and most of Mosul, securing its strategic position in the Persian Gulf. London also sought access to a Mediterranean port, selecting Haifa, which was connected to the Persian Gulf and Baghdad via Abu Kemal.

Ottoman Turkish Cartoon of 1910 Turkey taking on the European and Russian superpowers while China and japan look on /Alamy

Additionally, the report identified Palestine as a separate province, even though the region was divided between the vilayets of Syria and Beirut and the sanjak of Jerusalem under the Ottoman Empire. The committee recommended that Palestine’s future be determined through special negotiations. As a result, the de Bunsen Committee became the first British government body to formally address the future of Palestine.

Britain and the Arab National Liberation Movement

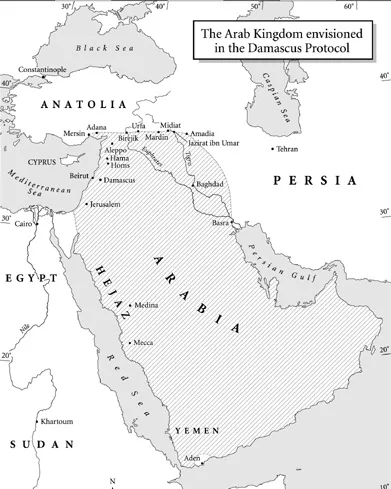

Around the same time that the de Bunsen Committee was outlining Britain's desideratum, its preferences and objectives, in the Middle East, members of Arab secret societies drafted the Damascus Protocol, which outlined the envisioned borders of a future independent Arab state. Even before the start of the First World War, leaders of the Arab nationalist movement had decided to seek independence from the Ottoman Empire. The British, eager to weaken Turkey’s position in the war, supported the idea of an Arab uprising and began negotiations with Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca, encouraging him to take up arms.

In the spring of 1915, Emir Faisal, Hussein’s son, visited Damascus, the center of the Arab national liberation movement, where the Damascus Protocol was drafted.

Bedouin leader and Ottoman officers in Damascus. At this time, Bedouin tribes in the region played a key role in military actions – some supported the Ottoman Empire, while others allied with the British and the French. 1915/ Library of Congress

The leaders of the movement agreed to support Hussein’s revolt on one condition: that he coordinate the borders of a future independent Arab state with Britain and secure its backing. The protocol outlined the creation of an Arab state—encompassing Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula but excluding Aden, which was under British control—within its ‘natural borders’.

Damascus Protocol Map/ECF (Economic Cooperation Foundation)

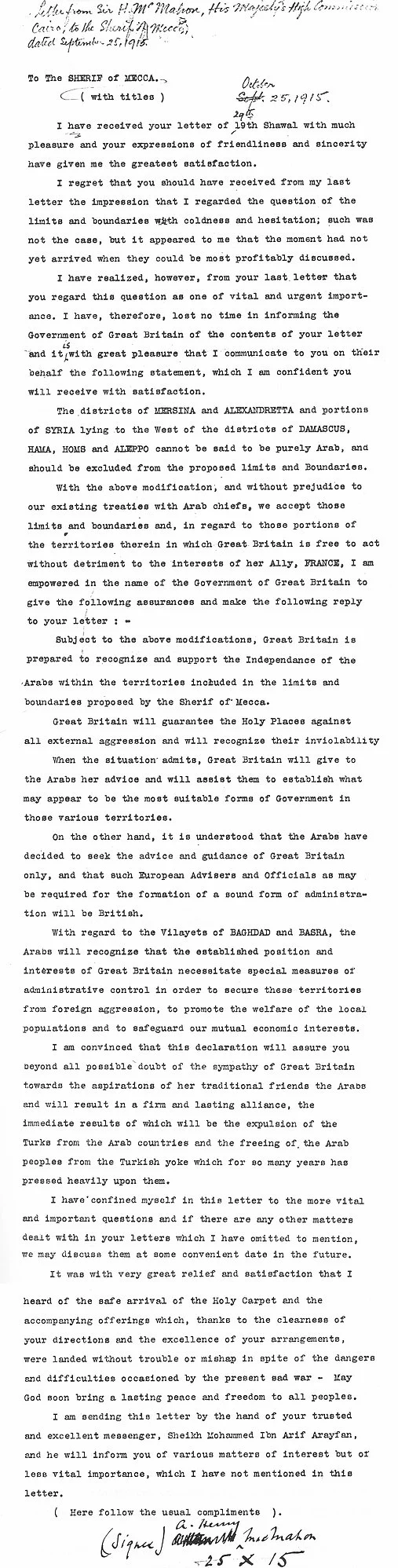

The Damascus Protocol became the basis for a letter Hussein sent to Henry McMahon, the British high commissioner in Egypt in July 1915. He outlined the conditions for Arab-British cooperation, emphasizing Britain’s interest in supporting Arab aspirations. Seeing Hussein as a potential ally, the British responded with vague territorial assurances. In a letter dated 24 October 1915, McMahon stated that Britain was willing to recognize Arab independence within the borders Hussein had proposed except for the British protectorates on the Arabian Peninsula and the territories west of Aleppo, Hama, Homs, and Damascus—meaning western Syria, Lebanon, and Ciliciai

McMahon–Hussein Letter 25 October 1915 /Wikimedia Commons

Palestine was not explicitly mentioned in the correspondence possibly because it was not considered a separate administrative unit. Hussein may have omitted it unintentionally, while McMahon deliberately avoided the subject to sidestep clear commitments. And thus, relying on McMahon’s promises, Hussein launched the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire in June 1916.

His son Faisal and British intelligence officer T.E Lawrence, who later became famous as Lawrence of Arabia, led the uprising. The revolt's success emboldened Hussein to proclaim himself king of the Arab nation in November 1916, aiming to unite all Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire. However, Britain and France only recognized him as king of Hejaz, postponing decisions on other territories until after the war. By that time, however, they had already begun secret negotiations on the division of the Middle East, misleading Hussein.

Thomas Edward Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and the Arab Revolt (1916–1918). In the center is Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Harithi, to his right is Emir Abdullah ibn Hussein al-Hashimi (son of the Sharif of Mecca Hussein ibn Ali, later King of Jordan), also present is Motlog al-Himrieh, an Arab commander/Wikimedia Commons

Britain and France: The Secret Partition of Territories

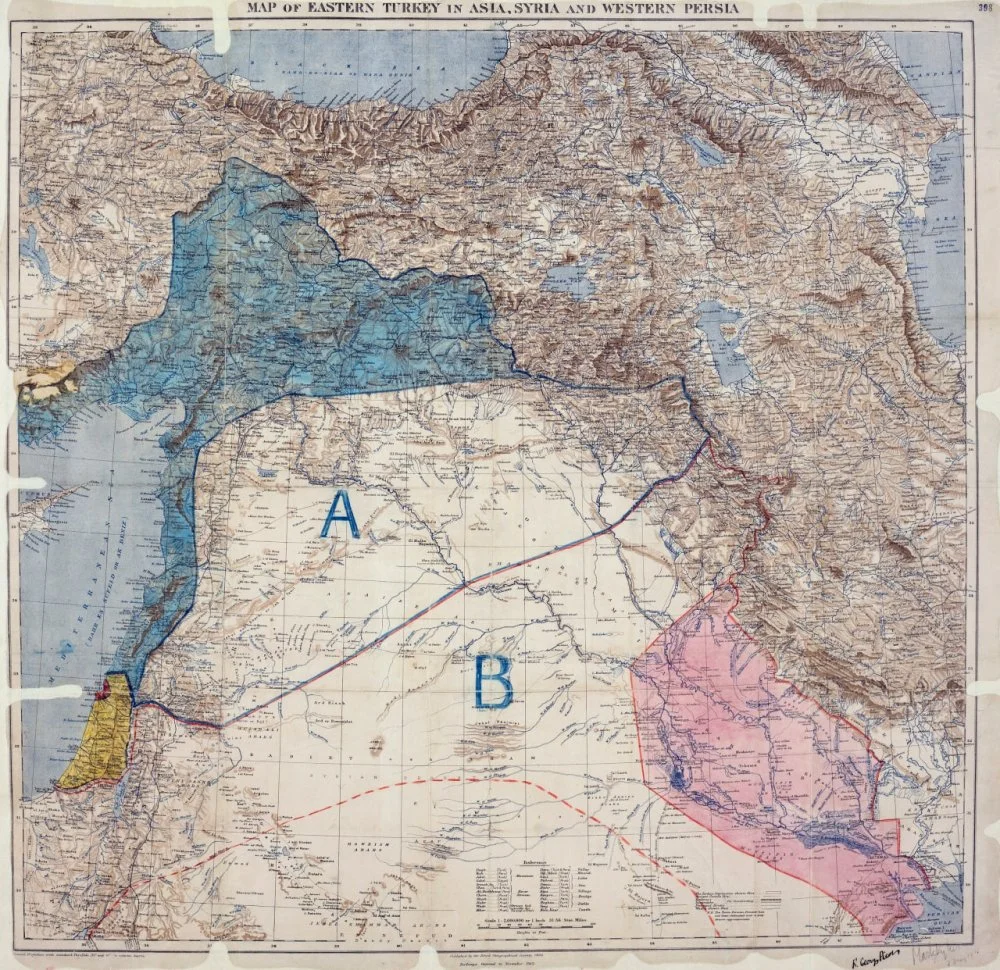

British government advisor Mark Sykes and former French consul François Georges-Picot led negotiations over the division of the Ottoman Empire’s Asian territories. In November 1915, they drew a boundary from Acre on the Mediterranean coast to Kirkuk in Iraq, calling it the E-K line, naming it after the last letter of the first city and the first letter of the second. Britain’s sphere of influence was south of this line, while the north fell under French control.

By 1916, Britain and France had agreed to divide the Middle East into zones of direct and indirect control. Britain was to receive central and southern Mesopotamia (including Baghdad and Basra) as well as the Palestinian ports of Haifa and Acre. France was granted western Syria, Lebanon, Cilicia, and southeastern Anatolia. Britain's zone of influence (Zone B) included Transjordan, southern Kurdistan, and southern Mesopotamia, while France’s (Zone A) covered eastern Syria and central Kurdistan, including Mosul. These territories were to form an ‘independent’ Arab state under joint British-French condominium rulei

Map showing Eastern Turkey in Asia, Syria and Western Persia, and areas of control and influence agreed upon between the British and the French. Royal Geographical Society, 1910-15. Signed by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, 8 May 1916/Wikimedia Commons

The Russian Empire also participated in the negotiations of the division of the Ottoman territories. According to the 1915 Franco-British-Russian agreement, following the anticipated victory of the Entente powersi

A plan to divide the Porte's holdings and establish spheres of influence and control in these Middle Eastern areas and zones under the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 following the supposed defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. The Russian zone is shown in green/Wikimedia Commons

Soon, Palestine became the most contentious territory in the negotiations. The French were reluctant to relinquish it as it was administratively part of Syria. At the same time, the British refused to withdraw, viewing control over Palestine as crucial to securing their hold over Egypt. As a compromise, Palestine (excluding the designated port enclaves) was placed under international control—an arrangement that satisfied neither side.

Shows three proposals for the mandate of Palestine. The red line refers to the "International Administration proposed in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, the dotted blue line is the 1919 Zionist Organization proposal at the Paris Peace Conference, and the blue line refers to the final borders of the 1923-48 British Mandate for Palestine/Wikimedia Commons

The Sykes-Picot Agreement directly contradicted the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. First, the ‘independent’ Arab state was to be established in territories under British and French influence, a condition that was never mentioned in McMahon’s agreements with Hussein. Second, Palestine, which the Arabs had intended to include in their state, was placed under international administration under Sykes-Picot.

Britain and the Zionist Movement

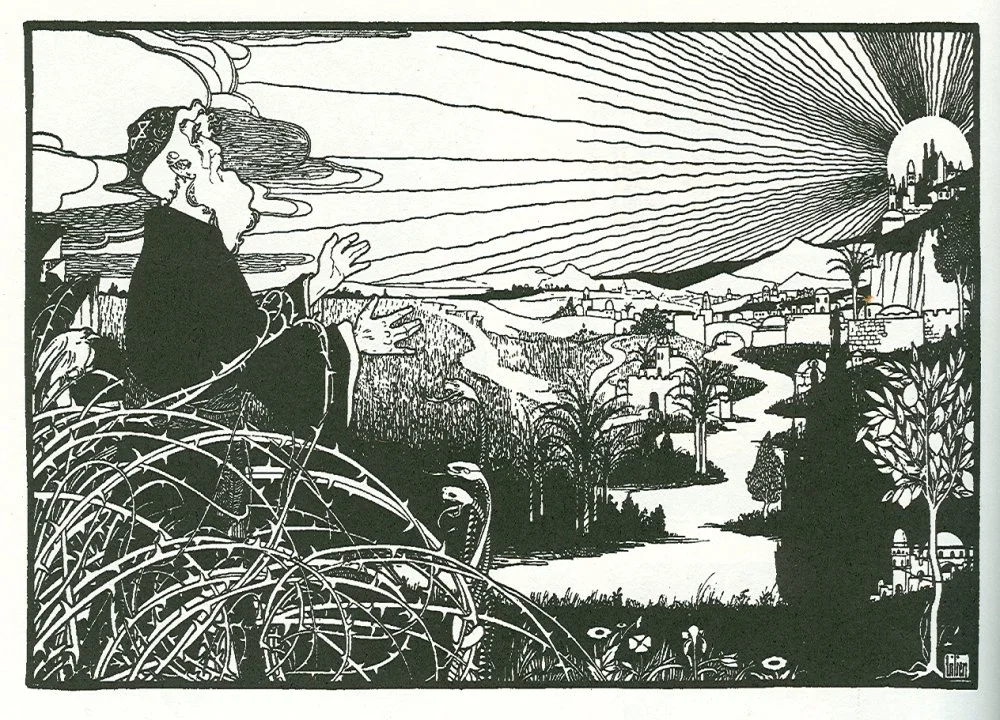

Britain also decided to support the Zionist movement, a sociopolitical movement that had emerged in late nineteenth-century Europe. The Zionists sought to revive Jewish national identity and establish a Jewish state in the historic land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael). As a first step, they aimed to create a Jewish ‘national home’—a significant and self-sustaining Jewish community—laying the groundwork for an eventual independent state.

Degania (later Degania Alef), sometimes considered the first kibbutz, in 1910/Wikimedia Commons

Chaim Weizmann, a professor at the University of Manchester, future head of the World Zionist Organization, and first president of Israel, became a prominent figure in the Zionist movement in Britain. During the First World War, he helped establish the domestic production of acetone, freeing Britain from dependence on foreign supplies, which brought him to the attention of politicians. Weizmann cultivated connections with the British elite, persuading them that establishing a Jewish national home in Palestine under British protection would strengthen their influence in the region.

Ephraim Moshe Lilien. Looking to the East. 1901/Wikimedia Commons

The British government saw Weizmann’s proposals as an opportunity to gain a new ally in the Middle East and justify its territorial ambitions to European powers. As a result, in November 1917, the Balfour Declaration—an official letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to the president of the British Zionist Organization, Lionel Rothschild—was issued. The letter expressed the British government’s support for ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’.

Lord Balfour's visit to Binyamin 1925. Sitting from left to right: Vera Weizman, Haim Weizman, Balfour, Nahum Sokolov. Standing: British Mandate officials and PKA officials (Henry Frank and Jules Rosenhack)/Wikimedia Commons

Though the declaration contained no concrete commitments, its official nature placed a certain responsibility on British policymakers. Considering that Britain’s agreements with the Arabs and the French were secret, the Balfour Declaration theoretically carried even greater obligations than those undisclosed treaties.

The Formation of the Mandate System

The publication of the Balfour Declaration and the revelation by Soviet Russia of the secret Sykes-Picot agreement shocked the Arab national liberation movement. To mitigate the consequences, Britain sent Hussein a memorandum assuring their support for an Arab state but excluding Palestine from its territory. Outraged, Hussein demanded confirmation of the agreements with McMahon, but London avoided a direct response.

After the 1918 armistice with the Ottoman Empire, the Entente Powers occupied their territories. Britain established a civil administration in Palestine and Mesopotamia, while France did the same thing in Lebanon, Western Syria, and Cilicia. An Arab administration was formed in Eastern Syria and Transjordan under Emir Faisal's leadership. However, the territorial division, according to the Sykes-Picot agreement, did not satisfy the Arabs, the French, or the British, who sought more.

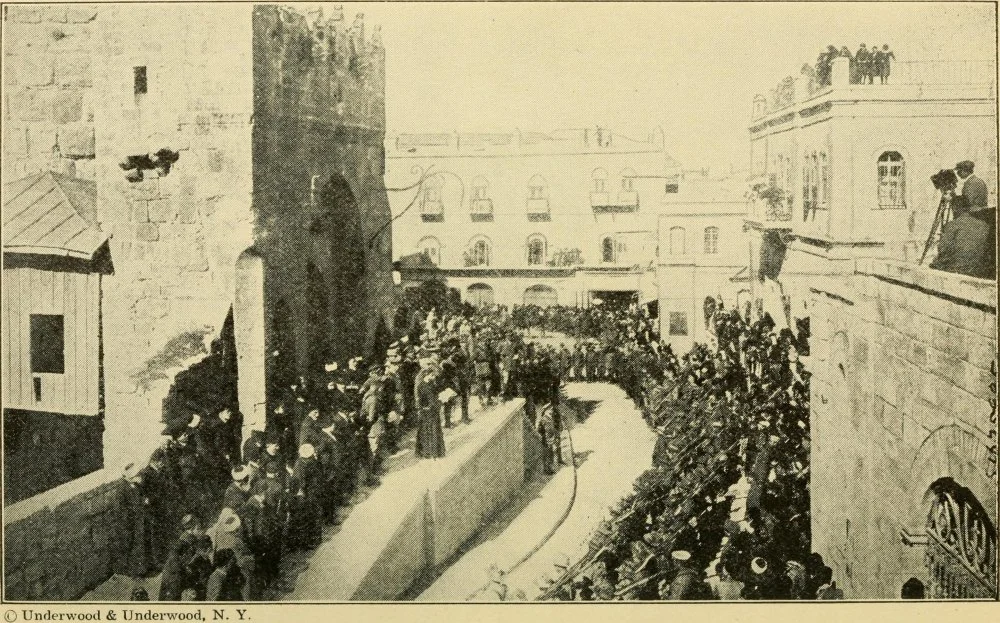

The Reading Of The Proclamation Of The British Occupation Of Palestine At The Tower Of David In Jerusalem 11 December 1917/Wikimedia Commons

In 1919, the Paris Peace Conference was convened to negotiate peace treaties with the defeated states. An Arab delegation headed by Emir Faisal, who still sought to create an Arab state, was also present at the conference. However, Faisal’s claims were not heard in Paris. Moreover, the British managed to secure his consent for the transfer of Palestine under their control.

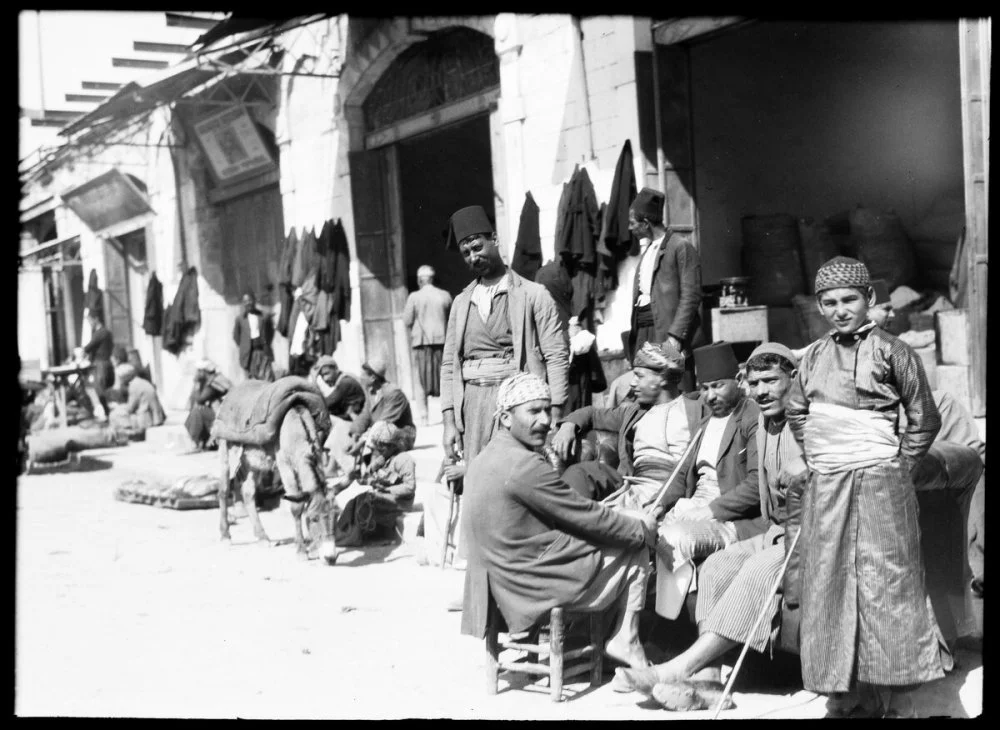

Palestinians-мусульмане in Jaffa in the 1920s/Wikimedia Commons

The Paris Conference adopted the League of Nations Covenant, which outlined the creation of the mandate system. In 1920, at a meeting of the Supreme Council of the Entente in San Remo, the decision was made to assign the mandates for Palestine (including Transjordan) and Mesopotamia to Britain and for Syria and Lebanon to France.

The Kingdom of Iraq

After receiving the mandate for Mesopotamia, British policymakers faced a serious question: how would they organize this heterogeneous territory? Historically, the Ottoman vilayets of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul were governed separately and differed significantly from each other. Basra had long-standing connections with the countries of the Persian Gulf, Baghdad was the center of transit trade for Iran, and Mosul had much in common with southern Turkey. Religious divisions between Sunnis and Shiites were compounded by the ethnic diversity of these territories as well as varying levels of socioeconomic and political development. However, none of this deterred the British from their desire to unite the three distinct provinces into a single entity.

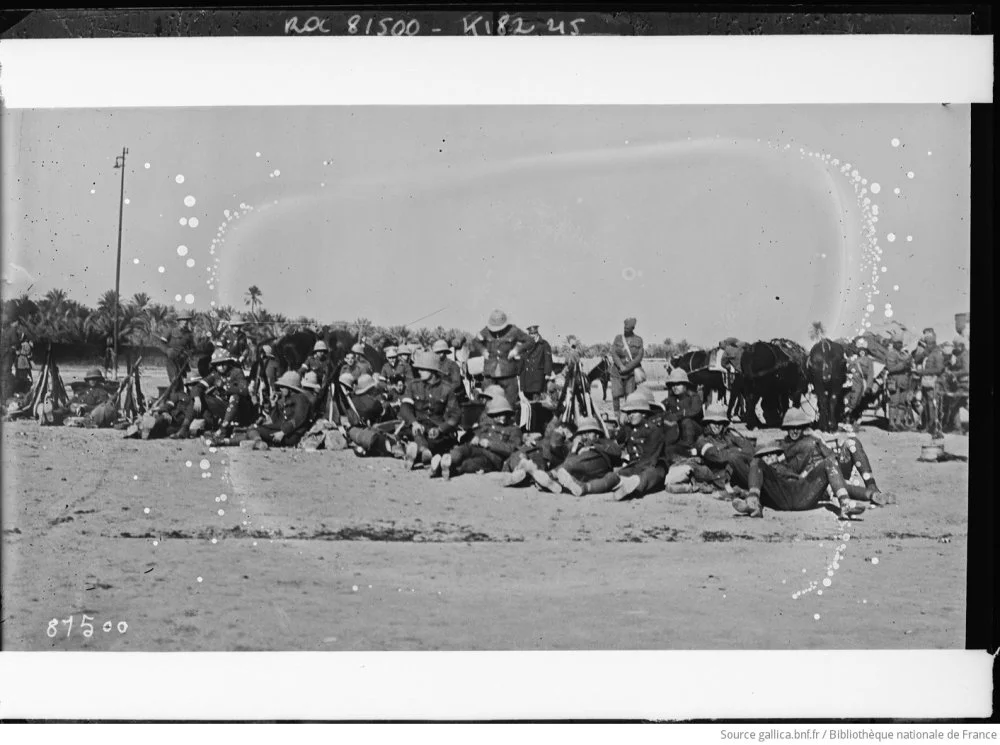

English soldiers near Mosul. 1920/Bibliothèque nationale de France

The local population was not only uninterested in the arrival of the British but also did not want to live within a single state. As a result, the decision to place Mesopotamia under a British mandate sparked widespread outrage, escalating into an armed uprising involving more than 130,000 people. Although the rebellion was suppressed, it forced the British administration to reconsider traditional forms of governance (protectorates and mandates) in favor of indirect methods—creating state entities in dependent territories and signing allied treaties with them.

At the Guildhall , London ; Lord Allenby , Emir Faisal , Mr Lloyd George and Lady Allenby . 7 October 1919/Alamy

Under such a treaty, Britain could maintain its troops and control the country's foreign policy and finances. Therefore, the British declared Iraq a mandated kingdom, and Faisal was crowned the king of Iraq. In 1922, a treaty of alliance was signed between Britain and Iraq, and ten years later, the British mandate in Iraq was formally canceled, although the country's independence remained conditional. In the years to come, this state would face numerous challenges. In fact, the consolidation of the diverse territories united by Britain into the entity known as Iraq remains incomplete to this day.

The Emergence of Transjordan

Transjordan, often described as an artificial but successful creation of Britain, was, before its establishment, an empty territory between Syria, Hejaz, Iraq, and Palestine. During the First World War, T.E. Lawrence convinced the sheiks of Transjordan to join the Arab Revolt. By September 1918, the Transjordanian tribes, as part of Emir Faisal's army, had liberated their lands from the Ottomans, and in October, they entered Damascus with British forces. There, Faisal formed an ‘Arab government’, which included Transjordan. However, at the Paris Conference, Faisal's claims to all the Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire were not recognized, and he attempted to create a Syrian-Transjordanian state, declaring himself king of the ‘United Syrian Kingdom’ in 1920. But the French, in agreement with Britain, quickly moved to remove him from power, and he later became the king of Iraq.

The Independence Movement in Syria: Demonstration against the French Mandate in Damascus , early 1920s/Bibliothèque nationale de France

After Faisal's expulsion, the Transjordanian fate remained uncertain. The situation was complicated by the fact that troops from Hejaz, led by Faisal's brother Emir Abdullah, had advanced into the region and captured its major cities. This unexpected development raised new questions about the future governance of the territory and Britain’s role in shaping its destiny. Abdullah was upset by Faisal's choice of Iraq and was now seeking his own throne.

In 1921, Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill met with Abdullah in Jerusalem, where he made it clear that neither Syria nor Palestine would be under Hashemite rule. Still, Abdullah had a chance to make his mark in Amman. Both Abdullah and the British came to a compromise, resulting in the creation of the Emirate of Transjordan. This territory was excluded from the scope of the Balfour Declaration—it remained under the British mandate administration but was separated from Palestine.

At the 1921 Cairo Conference, Britain discussed the future of the Middle East after the Ottoman Empire’s collapse, appointing Faisal as King of Iraq and Abdullah as Emir of Transjordan. Seated (front row): Field Marshal Lord Allenby, Winston Churchill and others//Wikimedia Commons

Abdullah, as the head of the emirate, was tasked with ‘preparing’ it for independence, receiving support from London, and committing not to interfere with the mandatory powers in Syria and Palestine. In 1928, the emirate, following Iraq's example, signed an alliance treaty with Britain. After the Second World War, Transjordan became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, initially ruled by an absolute monarch and later, a constitutional one.

The Fate of Palestine

A complex situation developed in Palestine. Unlike other mandated territories with Arab populations, the British authorities could not establish an Arab state in Palestine because such a step would have required renouncing the Balfour Declaration. The Declaration was fully incorporated into the text of the mandate for Palestine, which meant that Britain's commitments to the Zionist movement were given international legal standing to the detriment of promises previously made by British diplomacy to France and the Hashemite dynasty.

Britain's policy in Mandatory Palestine favored the formation of a new Jewish settler society, the Yishuv. For instance, Zionist organizations were helped to purchase estates from Arab feudal lords, which led to a reduction in the hiring of Arab labor and, combined with active Jewish immigration (120,000 Jews arrived in Palestine during the 1920s), increased hostility from the local Arab population.

Jewish pioneers building Balfour Street in Tel Aviv, 1921/Wikimedia Commons

In an attempt to appease the Arab side, in 1922, Colonial Secretary Churchill's ‘white paper’ was published, outlining the intention to limit Jewish immigration to Palestine in accordance with the interests of the population and the capacity of the economy. However, the influx of Jewish settlers did not cease, and the establishment of various Jewish institutions and structures continued at full speed.

By the end of the 1920s, uncompromising forces emerged on both the Jewish and Arab sides. These forces were decisive in the confrontation between Arab and Jewish religious radicals at the Western Wall in 1929. From that time, armed clashes between the two ethno-religious groups became a constant occurrence.

An Arab "protest gathering" in session, in the Rawdat el Maaref hall, 1929. From left to right : unknown – Amin al-Husayni – Musa al-Husayni – Raghib al-Nashashibi – unknown

After the start of the widespread Arab Revolt of 1936–39, demanding the end of the mandate, Britain began sending commissions to Palestine with the goal of developing plans for the division of the mandated territory. For instance, in its 1937 report, the Peel Commission proposed the idea of dividing Palestine into two independent states—an Arab state and a Jewish state. But both sides officially rejected this idea.

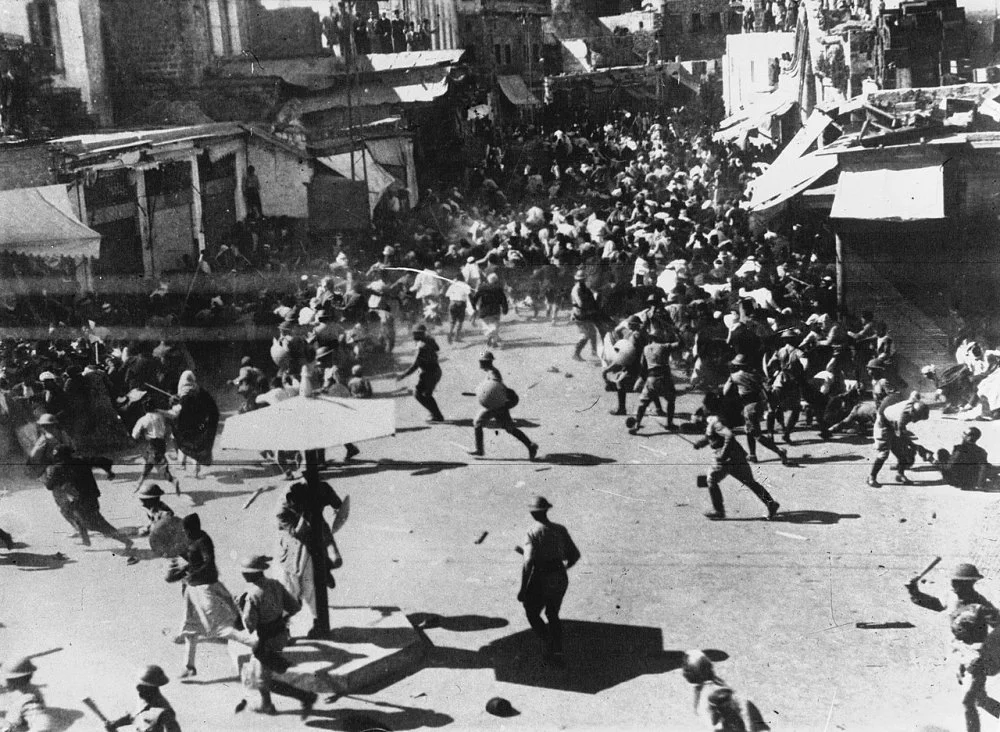

British policemen disperse an Arab mob during the Jaffa riots in April 1936 ("The Illustrated London News", 13. Juni 1936)/Wikimedia Commons

By the late 1930s, Britain decided to change its policy: in May 1939, another ‘white paper’ was published, the MacDonald Memorandum, which stipulated that, first, Palestine could not belong exclusively to either Jews or Arabs, and therefore, within ten years, the mandate would be terminated, and a joint Arab-Jewish state would be established. Second, quotas were set for Jewish immigration (75,000 people per year), and restrictions were imposed on land purchases by Jews. The Jewish community reacted very negatively to this document and began armed resistance against British authorities. It was only the onset of the Second World War that temporarily eased the intensity of the struggle. After the war, the conflict in the mandated territory of Palestine took on a completely different dimension.

Jewish demonstration against White Paper in Jerusalem in 1939/Wikimedia Commons

In just a few years, the British had completely reshaped the region's political map. Initially, their decisions—some carefully calculated, others hastily made—achieved their strategic goals: the Ottoman Empire was defeated, Britain expanded its territories and influence across the region, secured the Suez Canal, and gained access to Iraqi oil. However, the long-term consequences of British policies in the region were far more complex. The arbitrary borders drawn under the mandate system ignored deep-rooted ethnic, tribal, religious and sectarian divisions, sowing the seeds of great unrest in the future. By prioritizing imperial interests over local aspirations and realities, Britain helped create fragile states whose internal tensions and contested legitimacy continue to shape conflicts in the Middle East to this day.

Pro-Palestinian potestors against the war in Gaza march through Whitehall and Trafalgar Square in central London/Alamy

What to read

Всемирная история в 6 томах. Том 6: Мир в XX веке: эпоха глобальных трансформаций. Кн.1 / Отв. ред. А.О. Чубарьян. — М., 2017.

История Востока в шести томах. Том 5: Восток в новейшее время (1914–1945) / Отв. ред. Р.Г. Ланда / Институт Востоковедения РАН. — М., 2006.

Наумкин В. Кризис государств-наций на Ближнем Востоке // Международные процессы. Т. 15, № 2 (49), 2017.

Самарская Л.М. Декларация Бальфура в контексте англо-сионистской дипломатии в период Первой мировой войны / Институт Востоковедения РАН. — М., 2016.

Системная история международных отношений в четырех томах. Под ред. А.Д. Богатурова. Том 1: События (1918–1945). — М., 2000.

Fisher J. Curzon and British Imperialism in the Middle East (1916–1919). Frank Cass Publishers, 1999.

Mangold P. What the British Did: Two Centuries in the Middle East. I.B. Tauris, 2016.

Keilor W.R. The Twentieth-Century World: An International History. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Nevakivi J. Britain, France and the Arab Middle East (1914–1920). University of London, The Athlone Press, 1969.